With and without our headscarves, onwards to revolution!

Today, 17 December 2022, the people’s rebellion in Iran tending towards a revolutionary crisis has completed its third month. Jîna Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old Kurdish woman, was taken under custody by the “Guidance Police”, sometimes referred to as the “morality police”, for wearing her hijab “improperly” on 13 September 2022 and died on 16 September while still under custody.

On 17 September all hell broke loose in Iran.

The people of Iran, the Farsi and the Kurd, the Turk and the Arab and the Baloch, filled the streets and the squares, women at their head, and cried out loud “enough is enough”! Since that day Iran has been a bee hove in constant buzz and motion. Whether the repression increases, soaring with cold-blooded murder under the guise of the execution by hanging of the militants of the rebellion or whether concessions are granted, the people do not go back home. For the people want to bring down the regime.

The process Iran is going through will not only shape the future of Iran itself. It will, at the same time, influence profoundly the Middle East and North Africa region. Iran is the only country in the MENA region to have named a republic an “Islamic Republic”. That process has had an immense impact on the effervescence of Islamism in the entire region since 1979. Now that this regime is itself in crisis, the outcome of this crisis will surely have a serious reverse impact in the entire region.

Turkey and Iran share not only a long border of over 500 kilometres, but also a long common history and a profound cultural exchange that reaches back long centuries, a common problem with distinctive specific aspects in the area of Islamism vs. secularism, as well as the Kurdish question. So the Iranian revolutionary upheaval will have significant ramifications for Turkey as well.

DIP, the Revolutionary Workers Party of Turkey, celebrates the heroism and dignity of the Iranian people on the occasion of the completion of three months of a people’s rebellion. It declares its solidarity with this great revolutionary striving. The DIP has prepared a special dossier that covers different aspects of the revolutionary rebellion of Iran.

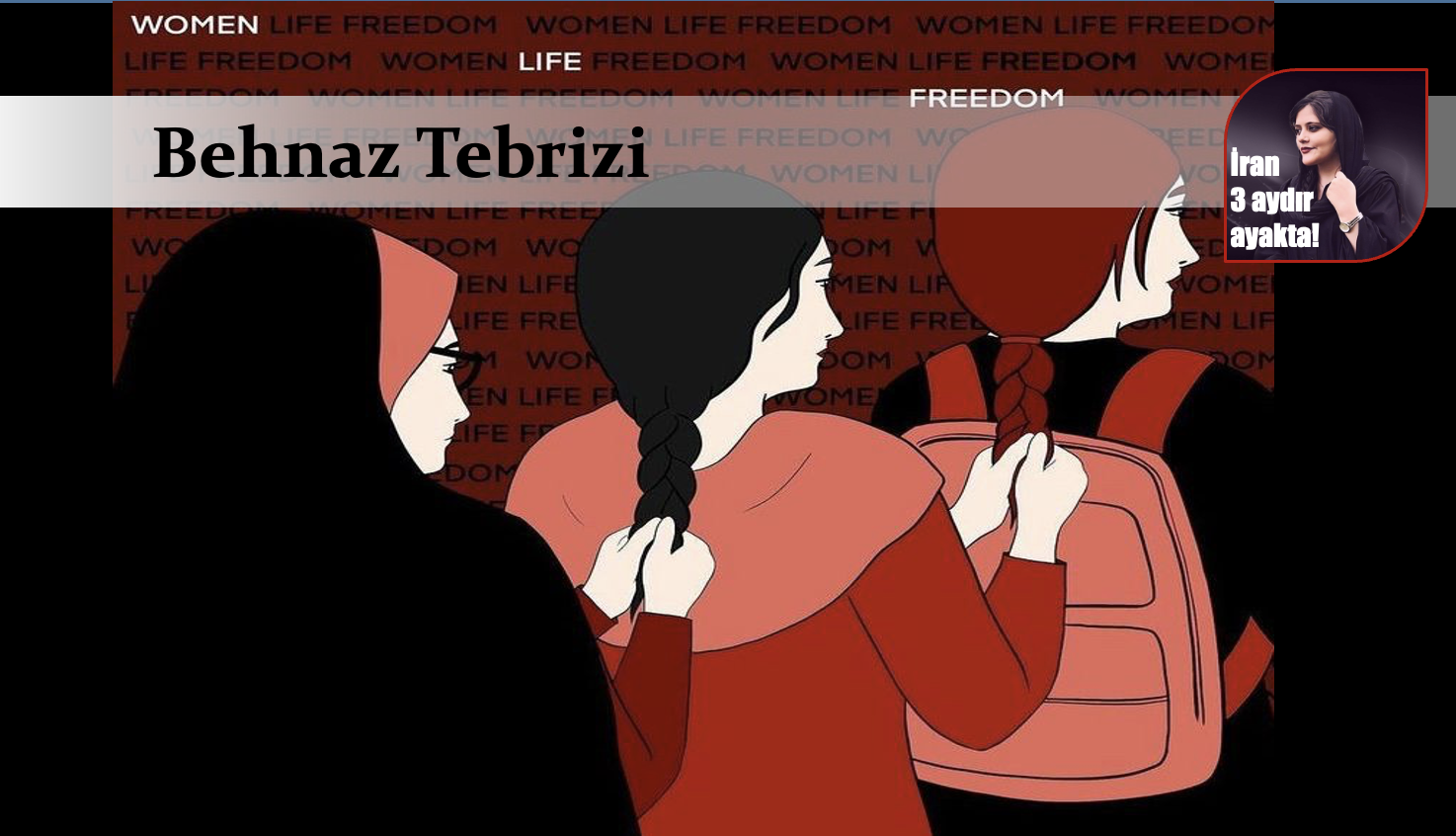

We kick off the dossier significantly with an article by our Iranian comrade Behnaz Tebrizi, who as a woman has had her share of the repression of the rights of women in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

DIP (Revolutionary Workers Party)

Iran became the only state with mandatory hijab after Saudi Arabia terminated its own practice in 2019. But how did this issue become such a thorn on the Iranian people? We will outline this process in this article.

The issue of hijab was put forward immediately after Khomeini usurped the leadership of the revolution. As a response, tens of thousands of women poured to the streets on March 8th of 1979 against the possibility of mandatory hijab. They chanted “we did not do this revolution for our rights to be taken back”. Khomeini stated that women could continue to work as before but from now on they had to dress according to Islamic principles. The practice of mandatory hijab started de-facto by removing female workers who did not dress “properly” from the workplaces. Thousands of women resigned to protest mandatory hijab. The massive protests following this were repressed violently and hundreds were jailed. In the beginning of the 1980s, proper hijab was legally defined by the government and all female workers were asked to obey it. It became a law in 1983, with the punishment of prison between 1 and 10 months and an accompanying 74 lashes for anyone offending the law.

This dark period led to murders of intellectuals, political infighting, exodus of many people on the opposition and the end of the uprisings against mandatory hijab. 1980s witnessed the creation of an Islamic Republic sanctioned style of hijab, and since then those with full veils and those without represented the two different sections of the society. The full black veil became the symbol of theocracy as a new kind of hijab and women had to cover themselves with them all the way from high schools to government offices. Such dress restrictions were not only meant for women, of course, the men also could not wear short sleeve shirts, jeans or shorts in public. It became de-facto mandatory for men to have long beards, especially for those in high government positions. Similarly, it was also mandatory for public sector workers to participate in Friday prayers and government organized demonstrations. Each government office, university or school was monitored by a special “security” unit. These units later combined to create the “national security organization”. These units were more concerned with the dresses of the workers, their participation in prayers, the length of their beards and whether they danced during weddings as opposed to national security and delivered warnings and punishments including removal from their jobs to those found lacking.

The laws related to mandatory hijab and dress restrictions were not results of a rigorous implementation of religious rules. Instead, they were implemented as a way to secure the Islamic Republic's domination over the society. Indeed, they were mechanisms meant to keep the mullah tyranny standing. This is why the regime reacts so violently whenever women initiate a struggle over this issue.

Easing

Since the end of 1990s, the exact interpretation of mandatory veils were left to the smallest local government units of municipalities. As such, black veils were no longer mandatory for public sector workers and students in many cities. In addition, the color codes for schools (limiting the allowed colors of dresses for students) were also annulled. Until the 2000s, it was forbidden to wear anything other than gray, black or brown clothes (including headscarves). But newer generations started going to the school with pink, red or green uniforms.

Internet and satellite technology were instrumental in the development of changing generations. The Iranian people started remembering the principles for which they fought and later forgot due to repression and the war. Of course, this change was not homogeneous in all regions. For example, the dresses used in northern Tehran (a more affluent part of the city) could not be used in the southern part. Likewise, public sector workers could freely work without beards in Tehran but they still felt the pressure in smaller cities. The “security inspections” done in job applications or university entrance, which mainly checked the proper religious behaviour of the applicants, were mostly annulled.

These new generations were not under the influence of the post 1978 repression, political executions, and the murders in the name of “cultural revolution”, and hence they were braver. Social media created a platform apart from reaction: a virtual society without headscarves. The relationship between men and women developed much more freely, and they could be friends without being lovers, previously a taboo (and these friendships could endure with the help of the internet). These generations also influenced their families.

A confession from the Islamic Republic

A few years ago, according to a statistic published by the Culture Ministry of Iran, 70% of Iranian people are against mandatory hijab. Hence today we witness the uprising of the 70%! 5% of the remaining 30% are day by day joining the majority against mandatory hijab. The theocratic tyranny not only breaks the faith of many faithful but also weakens the long-held view of religion being handed from generation to generation without any changes. Therefore, religion is more and more seen as a cultural element that can change over time. Today, the youth who are fighting against the regime in the streets are opposing the state mandated version of religion. They oppose the religious symbols put forward by the regime, because they represent the regime rather than religion itself. The Mullahs are no longer sacred and respectable religious figures of old, but are symbols of the regime and hence antagonized (we should mention here in passing that the regime also silences oppositional mullahs, therefore not all mullahs share the dominant viewpoint).

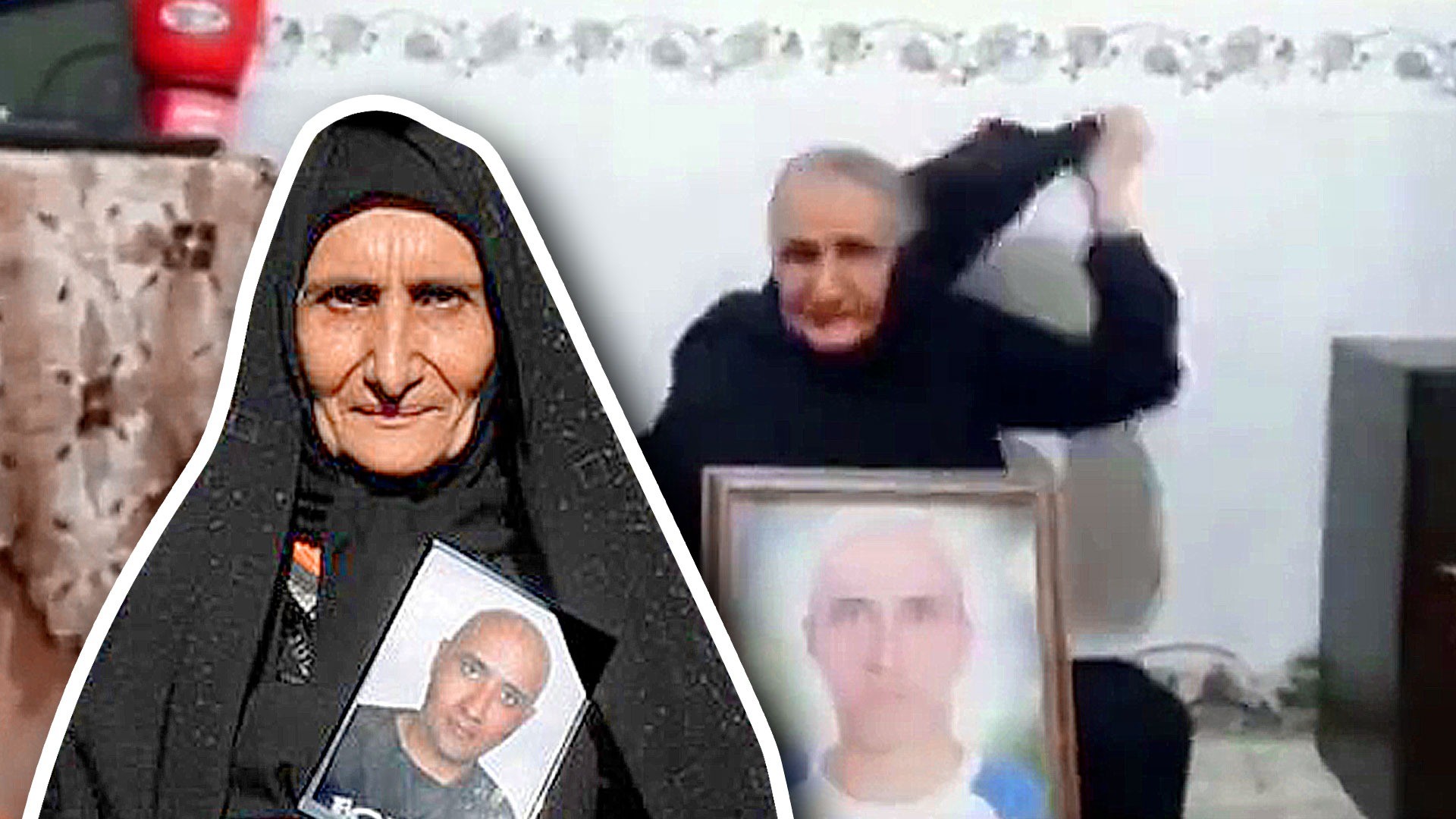

Our distinction between Islamic principles themselves and the Islamic Republic as an earthly, material tool for governing and repression is further validated through the struggle going on today. Together with young women who bravely remove their headscarves in public, as a symbol of disobedience against the tyranny, are relatively older women with their headscarves, fighting heroically side by side. For example, Gohar Eshgi, the mother of a worker and blogger who was murdered by the regime under torture, removed her full veil in front of cameras to support the demonstrators. Women of previous generations who do not actively participate in the demonstrations due to fear or other reasons, still support their daughters. This clearly shows that the Iranian people are not fighting against Islam. They are fighting against the Mullah tyranny, which exploits religion as a tool for repression and as a hegemonic ideology, and as such the Iranian people are fighting against the state.

This is a moment of a new round of separation of the worldly and the religious in Iran. A moment where religion and state should return to their own spheres. This is what is in the interest of the working class and the toilers. Achieving proletarian secularism through this struggle is one of the main responsibilities of the vanguard of the working class in countries like Iran.

Today Iranian women are in the streets chanting “With and without our headscarves, onwards to revolution!”. These uprisings are against the tyranny that systematically attacks women, working people, Sunni minority and non-Persian people in Iran.